Just before Christmas I opened my inbox and was disturbed to see this intriguing offer from Oxfam.

It was part of a drive to boost sales of Oxfam gift cards. These are cards that you give to someone to explain that as a present to them you have given a gift to a needy person in the developing world, in this case – a goat.

Why did this make me stop and think (and then decide to blog about it)?

…because I felt that it broke a cardinal aspect of good marketing: all brand messages should always act in accordance with their proposition.

Emotionally this offer clashed with my understanding of the proposition – the reasons that I had bought the cards before.

My problem…

I found myself facing a series of interlinked challenges:

- If I am giving a gift to someone that is simply a gift to a third person why would I want to halve the cost of the gift so that I save money? It undermines the value of the gift to me which is the gift to the charity.

- How does this help the person for whom the gift is intended. Surely a goat costs an amount of money and half that amount therefore only buys half a goat…so it is worth only half as much as a whole one?!

- How does this help Oxfam? If I want to buy goats for people at Christmas and they halve the cost of a goat, then, as I do not have more people to whom I want to give goats, surely the offer simply raises half as much money.

Even when I read the details more closely and realised that they had another donor who would pay for the ‘other half’ of the goat I was still suffering a real sense that this was a breach of the whole idea of giving a gift that is a donation to a third party. I felt that it was something that diluted the value not strengthened the value of the brand. Yes – it may encourage new buyers but then I was emailed and I am not a ‘new buyer’.

Hence this blog post: In a world of competing voices and hyper-competitive categories, diluting your proposition is to inflict wounds on your brand or idea and should be avoided at all costs. The key to doing this well is to put more effort into crafting your proposition.

The power of a strong proposition

The proposition is a fundamental strategic tool, the bedrock of marketing, and a touchstone for decisions on commercial policy and actions.

The clearer and the stronger that it is then the better for the organisation, brand or group that it speaks for. All brands have a proposition but too often people have not put the research or thought needed into it. This often leaves organisations with inconsistent or ineffective ones, or overly complex propositions that cannot be communicated clearly across the organisation (let alone to the outside world!).

A great example of the power of real thought and clarity can be seen in P&G’s approach to advertising strategy development. It is a discipline that helps to capture a ‘reason to believe’ in the brand which then anchors every marketing communication for the rest of its life. For new brands, an enormous amount of research and thought goes into creating a sustainable and powerful statement so that all the investment and activity that then supports a brand continually builds equity that lasts as long as possible.

The proposition captures the value that the brand brings to the world. It is it’s ‘reason for being’ and for sustaining and cannot, even in this age of personalised marketing, be all things to all people. Brands, or organisations, can offer multiple aspects of value – of relevance to different people, occasions and situations – but these must all be consistent with each other and over time. The energy and analysis that shapes them enables them to sustain and perform well in the face of competition.

Clear propositions work for us too…

Of course, a well-constructed proposition is not just of value in a straightforwardly commercial environment.

It provides the rationale to the outside world for any brand, group, body or even person. All groups, organisations and people have propositions. We spend a lot of time ‘selling’ in our lives in all sorts of contexts.

Daniel Pink reminded us of this in his book, To Sell is Human. Indeed, we all spend an enormous part of our lives selling, mostly in a non-sales environment, trying to persuade our children to do something (or not do something), people to volunteer their help, others to come with us to see this film or artist, go to that restaurant, do this activity, stop irritating us, talk to us etc. Every sale is made because someone ‘bought’ the proposition.

All groups, communities, individuals and activities have propositions. So it pays to make sure that, whatever you are responsible for, you have thought through its proposition and that you are clear about what it is.

What is a proposition?

To create a competitive and sustainable proposition there is a simple but vital question that needs to be answered:

Why should customers buy X … in preference to the alternatives (including doing nothing)?

This is in my experience is a remarkably powerful but difficult question to get a clear answer to for a brand. However, seeking a good answer for it provides a powerful direction and a guard against many different risks:

- It anchors our actions in customer insights. It explains why our actions are relevant to them at this moment

- It helps to push organisations to really be specific about who a proposition is for (and who it is not for)

- It steers groups to stay outward facing and not disappear into internal and ultimately non-value adding activities and concerns

- It provides a means of ensuring that actions remain consistent with what is best, across functions, geography and personalities

In doing so it can shape a mindset for the business – from customer service excellence at First Direct, or low cost at Aldi, to experience delivery at Apple or sound quality at Bose. The proposition can become a mantra to shape innovation, service delivery, product features and price positioning.

Creating a good proposition

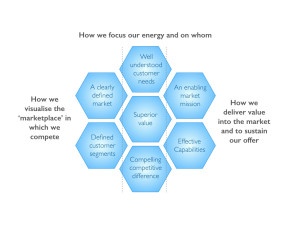

I use a framework to structure the areas to look at when thinking about what a proposition should be. This helps to frame the questions to be asked and the analysis to be undertaken in a way that helps organisations to create something that is an effective base. It is a honeycomb structure that pulls together 7 key elements for the task.

This framework helps to produce a proposition that is strong, relevant and sustainable. If you want to read more about this it is available on slideshare.

Conclusion

I did not buy into the half-price goats. However, I did buy some gift cards and even in the cold light of January I still don’t get the offer. I am sure it should read more like: ‘Buy one goat and get Oxfam one free too!’