The initial strategy in the Iraq 2003 invasion was described as ‘shock and awe’ (apparently technically it is called ‘rapid dominance’). The aim is to “overload an adversary’s perceptions and understanding of events such that the enemy would be incapable of resistance”.

The initial strategy in the Iraq 2003 invasion was described as ‘shock and awe’ (apparently technically it is called ‘rapid dominance’). The aim is to “overload an adversary’s perceptions and understanding of events such that the enemy would be incapable of resistance”.

It is a strategy to prompt a sharp change in behaviour.

It is a well established idea. The strategy was the justification for the use of the A-bomb at Hiroshima and Nagasaki; was articulated by Sun Tzu; and is seen as one factor in the success of the German battlefield strategy of ‘Blitzkrieg’.

The rationale is that shock overwhelms the natural optimism and resistance to bad news and enables a sharp shift in thinking. It is for this reason that sometimes leaders seek to follow a similar strategy: Find a shocking fact or idea, use it powerfully to generate high visibility and impact and so promote an urgent and vital change in behaviour.

You may, as a leader, feel that it is unlikely to be an approach that you would adopt. But it is more common than we might think and it is a favoured tactic for lobbyists, campaigners and politicians trying to move public opinion.

Most recently it has been used about global wealth inequalities (see Guardian). Similarly it has been sometimes used by environmental activists (on everything from fish stocks to carbon emissions), politicians (in warnings about extremist parties or Islamic terrorists) and business leaders (in turnaround situations).

The aim is to create fear or revulsion at what might happen and through this a change of heart.

But, in case you are tempted to follow suit when leading change – beware! The research suggests that it often reinforces resistance not undermines it. Indeed whilst it brought Japan to the negotiation table in 1945, it did not do this in Iraq.

Why is this?

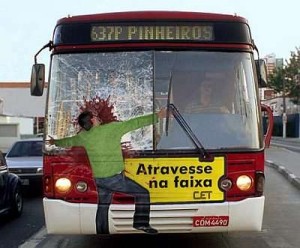

The insight comes from advertising, especially from the many charity and public information advertising campaigns that have used shock tactics. These include the UK Government’s ‘Kill your speed” to reduce speeding; “Think!” to encourage people to wear seatbelts; and Barnado’s campaign to raise money against child poverty. Shock has been one of the core strategies in this area. (For an entertaining selection of the most gruesome, have a look at the Guardian.)

Shock clearly attracts attention and without attention you cannot secure change. The Barnado’s press campaign used images of babies being fed through hypodermic needles or with bottles of meths. It generated more coverage and discussion on child poverty in 2 days than they had raised in the previous 2 years. Shock cuts through.

But attention is not action and the evidence is that a fear-provoking message on its own is unlikely to work. This is why health campaigners seeking to prevent alcohol, drug and tobacco adoption by young people no longer major on using these kind of messages.

Shock too easily raises the natural defences that stop behavioural change. You might aim to generate fear but instead provoke anger, puzzlement or guilt. None of which help change. Even if you provoke fear, this can cause people to freeze or dig deeper not change. But, apparently especially with younger people, it may simply be ignored as neither credible nor applicable to me (such as people not believing that an organisation in trouble will make ‘my’ role redundant, “I will not lose my job”).

So there are many reasons for shock tactics not to work as intended. No message lands on a blank canvas. People’s pre-existing views shape the impact. The result? Without supporting tactics and careful message crafting, it is unlikely to be productive.

So what are the keys to making sure a message works?

There are five things:

- Focus on creating emotional interest, identification, and urgency. These are the keys to making the message appear credible, applicable to me and urgent. This isn’t easy. It needs careful thought. It is very easy for us to avoid owning a problem and taking necessary action. Landing a message where there is a big problem that is a long way off, is tough. Sometimes a focus on the nearer issues is more effective – perhaps fish stocks and energy security versus climate change!

- Ensure your perceived remedy is effective. People will try to change the message if they do not perceive that they can readily address the underlying issue. The way forward and the credibility of the solution is critical and needs as much work as the shock message.

- Build up strong, visible support mechanisms. People need to believe that if they change, that they can succeed. For this, they need clear supporting mechanisms. Mechanisms that tip the balance to new behaviours. These might be increased penalties for not changing or greater help to move forward (e.g. giving away free needles or nicotine patches, increasing random breath tests or tighter smoking regulations).

- Encourage dialogue. A big bold message should not mean a big bold delivery with no right of reply. Leaders need to encourage dialogue, to enable people to engage with the challenge. This increases the credibility of the message. It helps people to interpret it more effectively and it only happens when people can contribute and own the challenge.

- Build resilience in your teams (i.e. better decision making, assertiveness and coping skills). People are better able to take on a big challenge with these skills. It makes it less likely that they reject a tough message. Working on these basic personal skills before and during a change can help the message be heard.

These five tactics help to make a real problem something to be tackled not something to be avoided in any way possible.