Contemplating a big change in direction but still implementing your current strategy?

Contemplating a big change in direction but still implementing your current strategy?

The expression ‘you should not change horses midstream’ apparently comes from a speech made by Abraham Lincoln in the 1864 presidential election as he urged voters not to switch leader in the middle of the civil war. It emphasises the risk in making a change with the idea of the danger of being washed downstream as you try to change the horse that is carrying you across a fast flowing river…

The uncertainty of change

It has stuck because it captures the risk of being sunk during a transition so well. Whether it be a change of policy, personnel, machine, strategy or even job we all sense the reality of this risk. To highlight but a few…

- A significant change almost always involves a monetary and time investment to bring it on-stream that is not easily made at the same time as running the operations in an organisation. It can derail cashflow or management attention.

- The future performance of a new strategy or job is almost always less certain than the performance of the current approach even if it is prospectively better in the longer term. There is no track record and it may take some time to tune it effectively. It may have hidden issues or teething problems.

- A drop in day-to-day performance exposes the organisation to risks (e.g. the loss of a key customer, missed profit target, staff discontent) that can be tough to recover from and of course, politically it also exposes the leader who instigates the change.

- It awakens political opportunism in others as a change disturbs power relationships in the organisation. It can then lead to at the least hassle and at worst a serious threat to your position.

All these seem good reasons for postponing a change where possible, especially if we are ‘midstream’. Sometimes it simply pays to stay in a not so good position to avoid an even worse one!

As we are all so much more sensitive to losses than gains, we can all behave like this. It can even be smart. We know transition is a big risk. Some smart leaders seem to prove this in the timing of their decision to move or retire from a long held position (e.g. in business or sports). All too often within the space of 12-18 months their successor can be fighting previously invisible issues, struggling with the transition and need to institute changes.

A common problem

What’s more this resistance to making changes happens in all walks of life…

In economics: It has a name – over-commitment. The relatively slow growth of the UK economy in the late Victorian period and beyond is often badged as a problem of over-commitment to traditional slow growth (and low skill) industries. There was an unwillingness to change horses to newer higher growth industries even when the returns from doing so were much better.

In business: I was working with Nokia in 2007 at the time that Apple launched its new smartphone and despite the obvious challenge of this change, few people in Nokia saw the need to change their strategy urgently. As a result they took too long to make any serious response to what became an organisation destroying innovation. Clayton Christensen’s landmark book ‘The Innovators Dilemma” captures the scale and significance of this phenomenon in organisations facing newdisruptive technologies.

In war: The rapid destruction of the allied defences in Western Europe in 1940 in the face of the innovative ‘Blitzkrieg’ tactics of armoured units was the result of a commitment to tactics that fitted the previous war when armour and communications were in their infancy.

In ourselves: We recognise it sometimes ourselves when we realise we have stayed in a role, place or organisation for too long.

If a change is not made soon enough then often it can become too late to make it at all.

However, our challenge is that this often means we should switch horses when we feel we are in the middle of things.

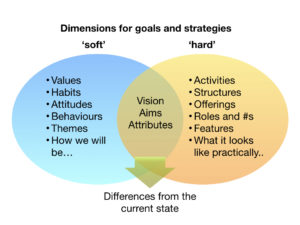

Four markers for switching horses now

So when should you decide to make this risky midstream change? What are the best signs that now is the time to move? When does ‘things are not going well’ translate into ‘now is the time’ to change?

Here are four markers that indicate now is the time to change for an organisation, group or even individual.

Any one on its own provides a good reason to change now but the presence of more than one is a strong imperative to do so and regular reflection on them might help to avoid the inevitable drowning that will take place if the horse you are using cannot make it across the stream.

- A significant gap in user experience

This is the first and in my mind most important sign.

A shortfall in the customers’ experience of you, your service or your organisation can often provide an important indicator of a need to change. It is a certainly a good time to question if things are still okay. The shortfall might be in comparison with alternatives (Nokia vs Apple smartphone) or against expectations (Sinclair C5, chocolate teapot) but where there is an evident and persistent gap of the sort that the average person notices then it is time to make a major change to address the challenge.

If users often come away with an underwhelming experience of me in a role, my organisation, or even if significant segments find a gap against competitive offerings, then this a sure sign that a change is needed now.

A good ‘outside-in’ perspective in the best test for change. Even after many years in consulting, it still amazes me how tough it can be in larger organisations for ‘outside-in’ insight to prompt real change. It is why it is vital to have in place ways that always keep leaders across the organisation involved and engaging with the ‘voice of the customer’.

As a person it is a great reason to pay attention and listen carefully to friends, colleagues and contacts. Wisdom so often comes from the outside.

2. A clear and present danger – a negative end game

This is not about the film but rather the principle. In the USA in 1919, the Supreme Court agreed to limits to the First Amendment freedoms based on this principle. In this case I suggest that it is a good test for change. When looking forward with your current strategy, approach, product, service etc if the game clearly does not end positively for you or the organisation then a change is needed.

In organisations this might be in terms of projections for revenues, margins, market share, staffing costs or the use of time (e.g. to manage downtime or close budgets) or again it might be external trends that are visible despite a current good performance. The growth of the online and mobile channels in retail is a case in point. The growth and impact of these were clear 10-15 years ago but it has taken many retailers until this decade to even begin to think about the impact on their own channels, property, methods, policies and range. The results can now be seen in their own performance – perhaps most strikingly in the way that this week the market value of Asos exceeded that of M&S for the first time.

3. No improvement options

Lets be clear -there are always improvement options. But sometimes when facing a performance challenge it can seem that you have run out of them. Everything that is suggested or tried seems impossible or does not seem to make a real impact or has major downsides and the only apparent decision is to ‘muddle through’ or hope for the best (which almost always means that everyone expects bad news!). This is time to make the jump to something radically different.

I have seen this where businesses are working with an operating or sales model that is no longer appropriate for their industry or competitive position and the pressure goes on staff in all manner of ways to improve performance but the reality is that trying harder is not really improving the position (and yet is burning people out at the same time!).

A default of just carrying on is not a real decision. This stuck-ness is a great indicator that a major change is needed.

4. Persistent negative trend

A consistent trend decline over months or years on key measures (e.g. revenue, market shares, productivity indices, profit, users, user sat, air quality etc) is another sign of the need to change. The challenge is, of course, what is ‘persistent’? How long does something need to be negative for it to qualify?

The answer definitely depends on context but much depends on what sort of a horizon you would normally take for a decision. For the insurance industry it might be a long time (ten years?), for a tech company it might be remarkably short (12 months?) but if the trend is an external one to the organisation and has not been reversed by repeated management action over a reasonable planning horizon then it is a good sign that a more fundamental change is needed now.

This also challenges leaders to identify good ‘leading’ indicators. Picking lagging measures will end up with you being too late to act. Yet surprisingly few organisations have good markers in place to enable this – especially in situations when markets are highly fragmented and data tough to come by.

Even when markers are in place, the dislike of unfavourable performance data is amazingly strong – witness the effort that goes into making figures look good in most corporates every quarter. One previous client of mine brazenly redefined their market to ensure that their share looked okay. Resistance to good feedback needs to be expected. This is why independent people and bodies (e.g. Office of Budget Responsibility) are a great help to make this work well and overcome the psychological obstacles.

Conclusion

The four markers for switching horses are useful. They help to build a case for change but I am also conscious that major decisions never solely depend on rational argument. Whether we like it or not there is a strong bias for the status quo and substance needs spin to land successfully.

So remember this and stretch to more creative tactics as well. I often sleep on analysis and then come back to it. This frequently brings a significant new insight or way to present it. Co-opting a black-hatted analyst or contrarian in the organisation or creating face-to-face discussions with negatively affected users also helps to unseat overly stubborn riders.

The challenge

The challenge

Contemplating a big change in direction but still implementing your current strategy?

Contemplating a big change in direction but still implementing your current strategy?